Nuclear Monitor #934

Lynda Williams, Community Voice, Honolulu Civil Beat

The Hawaiʻi State Energy Office has released the final report of the Nuclear Energy Working Group created by the Legislature under SCR-136. I served on the working group as a representative of 350 Hawaiʻi.

The report concludes that nuclear power is not viable in Hawaiʻi and that the state should not change its laws or Constitution to enable it.

The most fundamental obstacle is legal. Hawaiʻi’s Constitution restricts nuclear fission construction, and nuclear power is excluded from the state’s Renewable Portfolio Standard. These restrictions apply regardless of reactor size, design, fuel type, or branding. Small modular reactors and so-called “advanced” reactors are still nuclear fission reactors. Making nuclear power legal in Hawaiʻi would require amending the Constitution — a process that requires a two-thirds legislative vote. The working group did not recommend taking this step.

Beyond the law, the technology itself remains unfeasible. No advanced nuclear reactors are operating commercially in the United States, and none are expected to come online in any timeframe relevant to Hawaiʻi’s energy or climate goals. Projects cited by nuclear advocates remain stuck in licensing pipelines, demonstration phases, or heavily subsidized pilot programs. Without commercially operating reactors, reliable cost estimates, construction schedules, or grid-integration analyses do not exist. Nuclear power cannot meaningfully address climate change when it cannot be deployed at scale.

The report also acknowledges that radioactive waste is a decisive and unresolved problem. There is no permanent disposal repository operating anywhere in the United States. Hawaiʻi has no capacity to store or manage spent nuclear fuel, and no federal facility exists to accept it. The Hawaiʻi Constitution explicitly bars nuclear waste storage and disposal facilities unless approved by a two-thirds vote of both legislative chambers. Any nuclear project would therefore require indefinite on-island storage of radioactive material in direct conflict with the Constitution, creating ongoing risks related to containment failure and transport. For an isolated island state, this reality alone makes nuclear power unrealistic.

Emergency preparedness and regulatory capacity further reinforce that conclusion. Hawaiʻi does not have a nuclear regulatory agency, a trained nuclear emergency-response workforce, evacuation-planning capacity, or land suitable for exclusion zones. These are not minor administrative gaps. They reflect the absence of the institutional and physical capacity needed to respond to potentially catastrophic nuclear accidents.

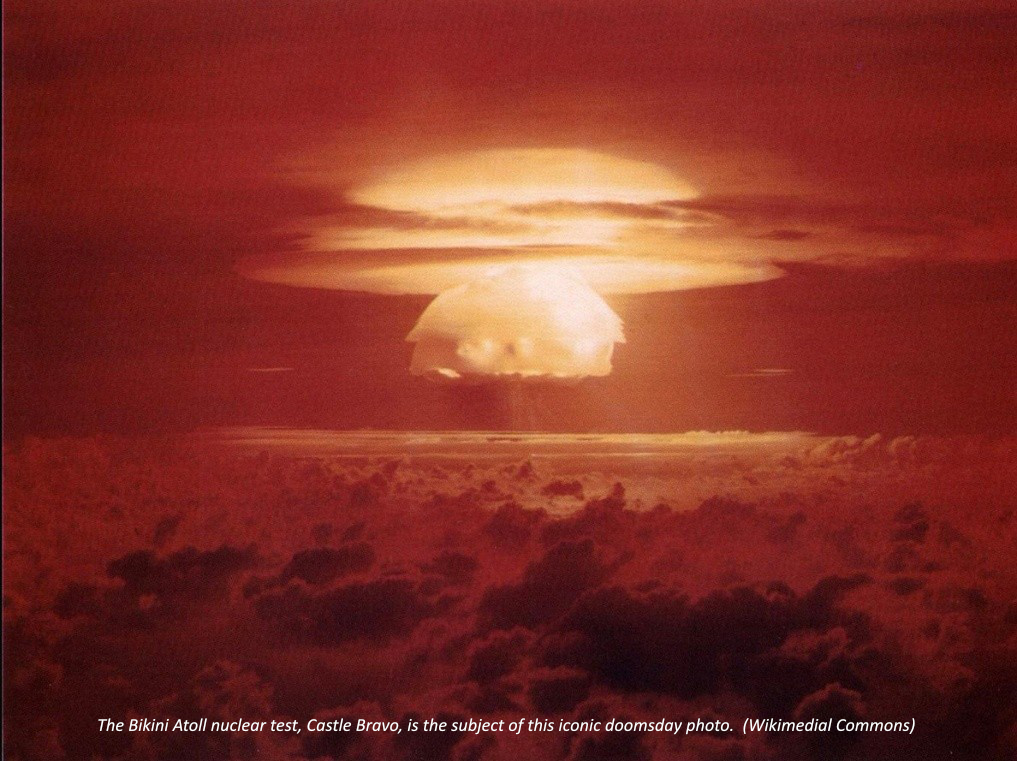

The analysis also places nuclear power in the context of Hawaiʻi’s history in the Pacific, including nuclear weapons testing and long-term harm to island and Indigenous communities. Public trust cannot be assumed, and meaningful public evaluation is impossible without concrete information about reactor designs, fuel cycles, waste handling, and accident scenarios — information that does not exist.

Hawaiʻi is not alone in facing industry efforts to dismantle state-level protections. Over the past decade, several states with laws restricting or prohibiting new nuclear plant construction — including Wisconsin, Kentucky, Montana, West Virginia, Connecticut, and Illinois — have repealed or weakened those laws to allow so-called advanced nuclear technologies such as small modular reactors (SMRs), often justified by climate or grid-reliability claims. These rollbacks occurred despite the continued absence of commercially operating advanced reactors, the lack of a permanent nuclear waste repository, and mounting evidence that nuclear power cannot be deployed fast enough to play a meaningful role in addressing climate change.

Now is not the time to weaken Hawaiʻi’s protections against nuclear power. At the federal level, environmental protection and public oversight under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) are being aggressively gutted through executive orders and legislation such as the SPEED Act. These measures are designed to shorten environmental review, eliminate meaningful public participation, restrict judicial oversight, and prevent courts from stopping unlawful projects even when agencies violate the law. As federal safeguards are dismantled, Hawaiʻi’s constitutional and statutory protections against nuclear power become more critical, not less.

The report’s only weak point is its suggestion that the state revisit nuclear power every three to five years. Even under the most optimistic assumptions, advanced nuclear reactors, including SMRs, will not be commercially operating, fully tested, or economically viable within that timeframe. Any nuclear reactor operated in Hawaiʻi would require radioactive waste to remain on island for extended periods to cool before transport, and shifting that waste burden onto other Indigenous lands is not an ethical solution and is inconsistent with the values of aloha ʻāina. Nuclear power is not viable in Hawaiʻi and never will be; the state should instead focus on renewable energy, storage, efficiency, grid modernization, and community-centered planning grounded in reality.

To read the final Nuclear Energy Working Group report, visit:

https://energy.hawaii.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/SCR136_AdvancedNuclearHawaii_2025LegReport.pdf

Lynda Williams is a physicist and journalist based in Hilo.

This article is reprinted with permission of the author and was firts published on substack.com, 6 January 2026.